NEW DELHI – Japan’s nuclear disaster has fueled fear and uncertainty among all of the world’s producers of nuclear power. For India, an energy-starved country, much is at stake.

NEW DELHI – Japan’s nuclear disaster has fueled fear and uncertainty among all of the world’s producers of nuclear power. For India, an energy-starved country, much is at stake.That fear factor has two main causes. Although nuclear power ranks as a “clean” source of energy, it is accompanied by the terrible shadow of nuclear war, which emerged from Japan’s last reckoning with nuclear catastrophe, 65 years ago at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and which lends it an automatic association with mass destruction and death. Moreover, the secrecy that attends all things “nuclear” has left people not knowing enough to feel confident.

The fear inspired by the Fukushima Daiichi disaster will be reflected in soaring costs for nuclear power worldwide, largely owing to demands for improved safety and the need to pay more to insure the potential risks. Indeed, nuclear plants are prone to a form of “panic transference.” Should a reactor of one design go wrong, all reactors of that type will be shut down instantly around the world.

India’s dilemma is this: it has 20 nuclear plants in operation, with an additional 23 on order. With the country desperately short of power, and requiring energy to grow, concerned citizens are asking if nuclear is still the answer for India.

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has cautiously announced that a “special safety review” of all plants will be undertaken. “Not enough,” say roughly 50 eminent Indians, who at the end of March demanded a “radical review” of the country’s entire nuclear-power policy for “appropriateness, safety, costs, and public acceptance.” The group also called for an “independent, transparent safety audit” of all nuclear facilities, to be undertaken with the “involvement of civil-society organizations and experts outside the Department of Atomic Energy.” Until then, there should be “a moratorium on all…nuclear activity” and “revocation of recent clearances.” This is as explicit as opposition can get.

How have other countries reacted? France, which is around 80% dependent on nuclear energy, and is a big exporter of nuclear-plant technology, initially avoided most of the global anti-nuclear concerns. But now it, too, is promising to draw the necessary lessons from the Japanese experience and upgrade its safety procedures, including a reassessment of the potential effects of natural disasters on nuclear-plant operations, conceding that the occurrence of more than one natural disaster simultaneously had not been considered previously.

China, which has 77 nuclear reactors at various stages of construction, planning, and discussion, has said that it will “review its program.” Though Russia has formally announced that it will go ahead with its program, former President Mikhail Gorbachev – on whose watch the Chernobyl meltdown occurred 25 years ago – is not so sanguine.

While the US is the principal exporter of reactors, it currently has just two under construction on its own territory. Denmark, Greece, Ireland, and Portugal are strongly anti-nuclear, and Switzerland has stopped all nuclear-power projects.

All of this will lead to cost evaluation and escalation. According to a study conducted by the former Indian government minister Arun Shourie, the price of uranium could rise to $140 per pound, close to its record high.

A change of much greater consequence concerns the price of reactors. Pre-Fukushima, a report from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), “The Future of Nuclear Power, 2003,” as well as a study by researchers at the University of Chicago, established that nuclear energy was 50-100% more expensive than energy from coal or gas. The report of the Working Group on Power of the Planning Commission of India puts the cost of energy from the country’s coal-based plants at about one-third lower than nuclear power, with gas 50% cheaper.

Energy security and public safety should be of equal importance in determining future policy on nuclear power. Indeed, experts like C. M. A. Nayar have said that the Fukushima accident “could have happened even if there was no tsunami.” Nayar suggests that it has long been known that the reactor’s design contained basic flaws, though only the Japanese authorities can verify this.

So, what is to be done? Clean energy at a time of global warming is obviously necessary. But so is the safety and security of humans, animals, and plants. India has set itself on a path of virtually doubling its nuclear-power output. This is deeply troubling, for India’s supply of nuclear fuel, technology, and reactors is almost entirely dependent on imports from manufacturers who refuse liability for any malfunction.

There is, of course, no single correct response that would simultaneously and uniformly deal with resource scarcity, fossil-fuel depletion, climate change, and the risks of nuclear power. A choice will ultimately need to be made about how to meet India’s energy demands.

At a minimum, a thorough reexamination and full public debate must precede the construction of any new nuclear plant. But the current emphasis on nuclear power must be objectively reassessed, and dependence on it thereafter reduced. With nuclear safety suddenly becoming a global imperative, the costs are simply too high to do otherwise.

Jaswant Singh, a former Indian finance minister, foreign minister, and defense minister, is the author of Jinnah: India – Partition – Independence.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2011.www.project-syndicate.org

For a podcast of this commentary in English, please use this link:

http://media.blubrry.com/ps/media.libsyn.com/media/ps/singh13.mp3

http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/singh13/English

- India has a flourishing and largely indigenous nuclear power program and expects to have 20,000 MWe nuclear capacity on line by 2020 and 63,000 MWe by 2032. It aims to supply 25% of electricity from nuclear power by 2050.

- Because India is outside the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty due to its weapons program, it was for 34 years largely excluded from trade in nuclear plant or materials, which has hampered its development of civil nuclear energy until 2009.

- Due to these trade bans and lack of indigenous uranium, India has uniquely been developing a nuclear fuel cycle to exploit its reserves of thorium.

- Now, foreign technology and fuel are expected to boost India's nuclear power plans considerably. All plants will have high indigenous engineering content.

- India has a vision of becoming a world leader in nuclear technology due to its expertise in fast reactors and thorium fuel cycle.

Nuclear power supplied 15.8 billion kWh (2.5%) of India's electricity in 2007 from 3.7 GWe (of 110 GWe total) capacity and after a dip in 2008-09 this will increase steadily as imported uranium becomes available and new plants come on line. In the year to March 2010, 22 billion kWh was forecast, and for the 2010-11 year 24 billion kWh is expected. For 2011-12, 32 billion kWh is now forecast. Some 300 reactor-years of operation had been achieved by mid 2009. India's fuel situation, with shortage of fossil fuels, is driving the nuclear investment for electricity, and 25% nuclear contribution is foreseen by 2050, when 1094 GWe of base-load capacity is expected to be required. Almost as much investment in the grid system as in power plants is necessary.

In 2006 almost US$ 9 billion was committed for power projects, including 9.35 GWe of new generating capacity, taking forward projects to 43.6 GWe and US$ 51 billion. In late 2009 the government said that it was confident that 62 GWe of new capacity would be added in the 11th 5-year plan to March 2012, and best efforts were being made to add 12.5 GWe on top of this, though only 18 GWe had been achieved by the mid point of October 2009, when 152 GWe was on line. The government's 12th 5-year plan for 2012-17 was targeting the addition of 100 GWe over the period. Three quarters of this would be coal- or lignite-fired, and only 3.4 GWe nuclear, including two imported 1000 MWe units at one site and two indigenous 700 MWe units at another.

A KPMG report in 2007 said that India needed to spend US$ 120-150 billion on power infrastructure over the next five years, including transmission and distribution (T&D). It said that T&D losses were some 30-40%, worth more than $6 billion per year. A 2010 estimate shows big differences among states, with some very high, and a national average of 27% T&D loss, well above the target 15% set in 2001 when the average figure was 34%.

The target since about 2004 has been for nuclear power to provide 20 GWe by 2020, but in 2007 the Prime Minister referred to this as "modest" and capable of being "doubled with the opening up of international cooperation." However, it is evident that even the 20 GWe target will require substantial uranium imports. Late in 2008 NPCIL projected 22 GWe on line by 2015, and the government was talking about having 50 GWe of nuclear power operating by 2050. Then in June 2009 NPCIL said it aimed for 60 GWe nuclear by 2032, including 40 GWe of PWR capacity and 7 GWe of new PHWR capacity, all fuelled by imported uranium. This target was reiterated late in 2010.

Longer term, the Atomic Energy Commission however envisages some 500 GWe nuclear on line by 2060, and has since speculated that the amount might be higher still: 600-700 GWe by 2050, providing half of all electricity.

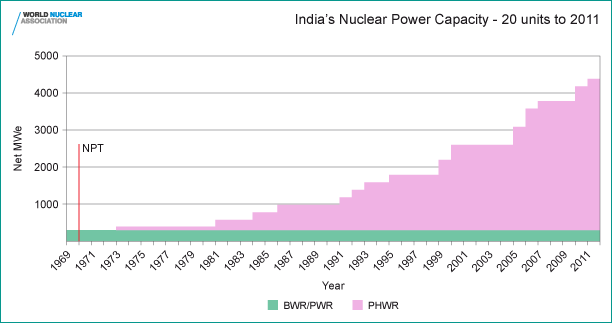

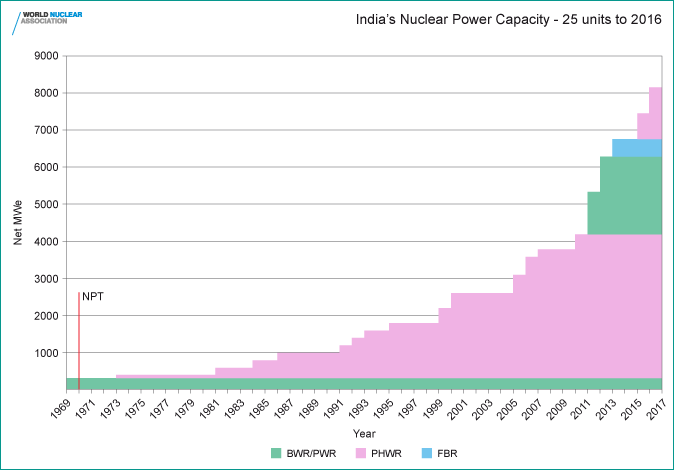

Indian nuclear power industry development

Nuclear power for civil use is well established in India. Its civil nuclear strategy has been directed towards complete independence in the nuclear fuel cycle, necessary because it is excluded from the 1970 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) due to it acquiring nuclear weapons capability after 1970. (Those five countries doing so before 1970 were accorded the status of Nuclear Weapons States under the NPT.)As a result, India's nuclear power program has proceeded largely without fuel or technological assistance from other countries (but see later section). Its power reactors to the mid 1990s had some of the world's lowest capacity factors, reflecting the technical difficulties of the country's isolation, but rose impressively from 60% in 1995 to 85% in 2001-02. Then in 2008-10 the load factors dropped due to shortage of uranium fuel.

India's nuclear energy self-sufficiency extended from uranium exploration and mining through fuel fabrication, heavy water production, reactor design and construction, to reprocessing and waste management. It has a small fast breeder reactor and is building a much larger one. It is also developing technology to utilise its abundant resources of thorium as a nuclear fuel.

The Atomic Energy Establishment was set up at Trombay, near Mumbai, in 1957 and renamed as Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) ten years later. Plans for building the first Pressurised Heavy Water Reactor (PHWR) were finalised in 1964, and this prototype - Rajasthan-1, which had Canada's Douglas Point reactor as a reference unit, was built as a collaborative venture between Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd (AECL) and NPCIL. It started up in 1972 and was duplicated Subsequent indigenous PHWR development has been based on these units.

The Indian Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) is the main policy body.

The Nuclear Power Corporation of India Ltd (NPCIL) is responsible for design, construction, commissioning and operation of thermal nuclear power plants. At the start of 2010 it said it had enough cash on hand for 10,000 MWe of new plant. Its funding model is 70% equity and 30% debt financing. However, it is aiming to involve other public sector and private corporations in future nuclear power expansion, notably National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) - see subsection below. NTPC is largely government-owned, and the 1962 Atomic Energy Act prohibits private control of nuclear power generation, though it allows minority investment. As of late 2010 the government had no intention of changing this to allow greater private equity in nuclear plants.

India's operating nuclear power reactors:

| Reactor | State | Type | MWe net, each | Commercial operation | Safeguards status |

| Tarapur 1 & 2 | Maharashtra | BWR | 150 | 1969 | item-specific |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaiga 1 & 2 | Karnataka | PHWR | 202 | 1999-2000 | |

| Kaiga 3 & 4 | Karnataka | PHWR | 202 | 2007, (due 2011) | |

| Kakrapar 1 & 2 | Gujarat | PHWR | 202 | 1993-95 | December 2010 under new agreement |

| Madras 1 & 2 (MAPS) | Tamil Nadu | PHWR | 202 | 1984-86 | |

| Narora 1 & 2 | Uttar Pradesh | PHWR | 202 | 1991-92 | in 2014 under new agreement |

| Rajasthan 1 | Rajasthan | PHWR | 90 | 1973 | item-specific |

| Rajasthan 2 | Rajasthan | PHWR | 187 | 1981 | item-specific |

| Rajasthan 3 & 4 | Rajasthan | PHWR | 202 | 1999-2000 | early 2010 under new agreement |

| Rajasthan 5 & 6 | Rajasthan | PHWR | 202 | Feb & April 2010 | Oct 2009 under new agreement |

| Tarapur 3 & 4 | Maharashtra | PHWR | 490 | 2006, 05 | |

| Total (20) | 4385 MWe |

Madras (MAPS) also known as Kalpakkam

Rajasthan/RAPS is located at Rawatbhata and sometimes called that

Kaiga = KGS, Kakrapar = KAPS, Narora = NAPS

dates are for start of commercial operation.

Rajasthan/RAPS is located at Rawatbhata and sometimes called that

Kaiga = KGS, Kakrapar = KAPS, Narora = NAPS

dates are for start of commercial operation.

The two small Canadian (Candu) PHWRs at Rajasthan nuclear power plant started up in 1972 & 1980, and are also under safeguards. Rajasthan-1 was down-rated early in its life and has operated very little since 2002 due to ongoing problems and has been shut down since 2004 as the government considers its future. Rajasthan-2 was restarted in September 2009 after major refurbishment, and running on imported uranium at full rated power.

The 220 MWe PHWRs (202 MWe net) were indigenously designed and constructed by NPCIL, based on a Canadian design.

The Madras (MAPS) reactors were refurbished in 2002-03 and 2004-05 and their capacity restored to 220 MWe gross (from 170). Much of the core of each reactor was replaced, and the lifespans extended to 2033/36.

Kakrapar unit 1 was fully refurbished and upgraded in 2009-10, after 16 years operation, as was Narora-2, with cooling channel (calandria tube) replacement.

More recent nuclear power developments in India

The Tarapur 3&4 reactors of 540 MWe gross (490 MWe net) were developed indigenously from the 220 MWe (gross) model PHWR and were built by NPCIL.The first - Tarapur 4 - was connected to the grid in June 2005 and started commercial operation in September. Tarapur-4's criticality came five years after pouring first concrete and seven months ahead of schedule. Its twin - unit 3 - was about a year behind it and was connected to the grid in June 2006 with commercial operation in August, five months ahead of schedule.

Future indigenous PHWR reactors will be 700 MWe gross (640 MWe net). The first four will be built at Kakrapar and Rajasthan. Work has started on all four sites and they are due on line by 2017 after 60 months construction from first concrete to criticality.

Russia's Atomstroyexport is building the country's first large nuclear power plant, comprising two VVER-1000 (V-392) reactors, under a Russian-financed US$ 3 billion contract. A long-term credit facility covers about half the cost of the plant. The AES-92 units at Kudankulam in Tamil Nadu state are being built by NPCIL and will be commissioned and operated by NPCIL under IAEA safeguards. The turbines are made by Leningrad Metal Works. Unlike other Atomstroyexport projects such as in Iran, there have been only about 80 Russian supervisory staff on the job.

Russia is supplying all the enriched fuel through the life of the plant, though India will reprocess it and keep the plutonium. The first unit was due to start supplying power in March 2008 and go into commercial operation late in 2008, but this schedule has slipped by more than three years. It is now due to start up in April 2011. The second unit is about 6-8 months behind it. While the first core load of fuel was delivered early in 2008 there have been delays in supply of some equipment and documentation. Control system documentation was delivered late, and when reviewed by NPCIL it showed up the need for significant refining and even reworking some aspects.

A small desalination plant is associated with the Kudankulam plant to produce 426 m3/hr for it using 4-stage multi-vacuum compression (MVC) technology. Another RO plant is in operations to supply local township needs.

Under plans for the India-specific safeguards to be administered by the IAEA in relation to the civil-military separation plan, eight further reactors will be safeguarded (beyond Tarapur 1&2, Rajasthan 1&2, and Kudankulam 1&2): Rajasthan 3&4 by 2010, Rajasthan 5&6 by 2008, Kakrapar 1&2 by 2012 and Narora 1&2 by 2014.

India's nuclear power reactors under construction:

| Reactor | Type | MWe gross, each | Project control | Commercial operation due | Safeguards status |

| Kudankulam 1 | PWR (VVER) | 1000 | NPCIL | mid 2011? (start-up in April) | item-specific |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kudankulam 2 | PWR (VVER) | 1000 | NPCIL | late 2011? | item-specific |

| Kalpakkam PFBR | FBR | 500 | Bhavini | 9/2011, or 2012 | - |

| Kakrapar 3 | PHWR | 700 | NPCIL | 2015 | |

| Kakrapar 4 | PHWR | 700 | NPCIL | 2016 | |

| Total (5) | 3650 MWe net, 3900 MWe gross |

Rajasthan/RAPS also known as Rawatbhata

Kaiga 3 started up in February, was connected to the grid in April and went into commercial operation in May 2007. Unit 4 started up in November 2010 and was grid-connected in January 2011, but is about 30 months behind original schedule due to shortage of uranium. The Kaiga units are not under UN safeguards, so cannot use imported uranium. RAPP-5 started up in November 2009, using imported Russian fuel, and in December it was connected to the northern grid. RAPP-6 started up in January 2010 and was grid connected at the end of March. Both are now in commercial operation.

In mid 2008 Indian nuclear power plants were running at about half of capacity due to a chronic shortage of fuel. The situation was expected to persist for several years if the civil nuclear agreement faltered, though some easing in 2008 was due to the new Turamdih mill in Jharkhand state coming on line (the mine there was already operating). Political opposition has delayed new mines in Jharkhand, Meghalaya and Andhra Pradesh.

A 500 MWe prototype fast breeder reactor (PFBR) is under construction at Kalpakkam near Madras by BHAVINI (Bharatiya Nabhikiya Vidyut Nigam Ltd), a government enterprise set up under DAE to focus on FBRs. It was expected to start up about the end of 2010 and produce power in 2011, but this schedule appears to be delayed about 12-15 months. Four further oxide-fuel fast reactors are envisaged but slightly redesigned by the Indira Gandhi Centre to reduce capital cost. One pair will be at Kalpakkam, two more elsewhere. (See also section below.)

In contrast to the situation in the 1990s, most reactors under construction are on schedule (apart from fuel shortages 2007-09), and the first two - Tarapur 3 & 4 – were slightly increased in capacity. These and future planned ones were 450 (now 490) MWe versions of the 202 MWe domestic products. Beyond them and the last three 202 MWe units, future units will be nominal 700 MWe.

The government envisages setting up about ten PHWRs of 700 MWe capacity to about 2023, fuelled by indigenous uranium, as stage 1 of its nuclear program. Stage 2 - four 500 MWe FBRs - will be concurrent.

Construction costs of reactors as reported by AEC are about $1200 per kilowatt for Tarapur 3 & 4 (540 MWe), $1300/kW for Kaiga 3 & 4 (220 MWe) and expected $1700/kW for the 700 MWe PHWRs with 60-year life expectancy.

Nuclear industry developments in India beyond the trade restrictions

Following the Nuclear Suppliers' Group agreement which was achieved in September 2008, the scope for supply of both reactors and fuel from suppliers in other countries opened up. Civil nuclear cooperation agreements have been signed with the USA, Russia, France, UK, South Korea and Canada, as well as Argentina, Kazakhstan, Mongolia and Namibia.The Russian PWR types were apart from India's three-stage plan for nuclear power and were simply to increase generating capacity more rapidly. Now there are plans for eight 1000 MWe units at the Kudankulam site, and in January 2007 a memorandum of understanding was signed for Russia to build four more there, as well as others elsewhere in India. A further such agreement was signed in December 2010, and Rosatom announced that it expected to build no less than 18 reactors in India. The new units are expected to be the larger 1200 MWe AES-2006 versions of the first two. Russia is reported to have offered a 30% discount on the $2-billion price tag for each of the phase 2 Kudankulam reactors. This is based on plans to start serial production of reactors for the Indian nuclear industry, with much of the equipment and components proposed to be manufactured in India, thereby bringing down costs. Rosatom has published a proposed schedule for Kudankulam phase 2, involving financing agreement mid 2010, EPC contract by end of 2010, and first concrete in June 2011.

Between 2010 and 2020, further construction is expected to take total gross capacity to 21,180 MWe. The nuclear capacity target is part of national energy policy. This planned increment includes those set out in the Table below including the initial 300 MWe Advanced Heavy Water Reactor (AHWR). The benchmark capital cost sanctioned by DAE for imported units is quoted at $1600 per kilowatt.

In 2005 four sites were approved for eight new reactors. Two of the sites - Kakrapar and Rajasthan, would have 700 MWe indigenous PHWR units, Kudankulam would have imported 1000 or 1200 MWe light water reactors alongside the two being built there by Russia, and the fourth site was greenfield for two 1000 MWe LWR units - Jaitapur (Jaithalpur) in the Ratnagiri district of Maharashtra state, on the west coast. The plan has since expanded to six 1600 MWe EPR units here.

NPCIL had meetings and technical discussions with three major reactor suppliers - Areva of France, GE-Hitachi and Westinghouse Electric Corporation of the USA for supply of reactors for these projects and for new units at Kaiga. These resulted in more formal agreements with each reactor supplier early in 2009, as mentioned below.

In April 2007 the government gave approval for the first four of these eight units: Kakrapar 3 & 4 and Rajasthan 7 & 8, using indigenous technology. In mid 2009 construction approval was confirmed, and late in 2009 the finance for them was approved. Site works at Kakrapar were completed by August 2010. First concrete for Kakrapar 3 & 4 was in November 2010, after Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB) approval. The AERB approved Rajasthan 7 & 8 in August 2010, and site works then began. First concrete is expected in December and construction is then expected to take 66 months to commercial operation. Their estimated cost is Rs 123.2 billion ($2.6 billion). In September 2009 L&T secured an order for four steam generators for Rajasthan 7 & 8, having already supplied similar ones for Kakrapar 3 & 4.

In late 2008 NPCIL announced that as part of the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-12), it would start site work for 12 reactors including the rest of the eight PHWRs of 700 MWe each, three or four fast breeder reactors and one 300 MWe advanced heavy water reactor in 2009. NPCIL said that "India is now focusing on capacity addition through indigenisation" with progressively higher local content for imported designs, up to 80%. Looking further ahead its augmentation plan included construction of 25-30 light water reactors of at least 1000 MWe by 2030.

The AEC has said that India now has "a significant technological capability in PWRs and NPCIL has worked out a 600-700 MWe Indian PWR design" which will be unveiled soon - perhaps 2010. Development of this is projected through to 2018, with construction of an initial unit starting in 2020.

Meanwhile, NPCIL is offering both 220 and 540 MWe PHWRs for export, in markets requiring small- to medium-sized reactors.

Power reactors planned or firmly proposed

| Reactor | State | Type | MWe gross, each | Project control | Start construction | Start operation |

| Rajasthan 7 | Rajasthan | PHWR | 700 | NPCIL | Dec 2010 | June 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rajasthan 8 | Rajasthan | PHWR | 700 | NPCIL | 2011 | Dec 2016 |

| Kudankulam 3 | Tamil Nadu | PWR - AES 92 or AES-2006 | 1050-1200 | NPCIL | 6/2011 | 2016 |

| Kudankulam 4 | Tamil Nadu | PWR - AES 92 or AES-2006 | 1050-1200 | NPCIL | 2012? | 2017 |

| Jaitapur 1 & 2 | Maharashtra | PWR - EPR | 1700 | NPCIL | 2013 | 2018-19 |

| Kaiga 5 & 6 | Karnataka | PWR | 1000/1500 | NPCIL | by 2012 | |

| Kudankulam 5 & 6 | Tamil Nadu | PWR - AES 92 or AES-2006 | 1050-1200 | NPCIL | 2014 | 2019-21 |

| Kumharia 1-4 | Haryana | PHWR x 4 (or x2) | 700 | NPCIL or NPCIL-NTPC | by 2012? | |

| Bargi 1 & 2 | Madhya Pradesh | PHWR x 2 | 700 | NPCIL or NPCIL-NTPC | 2012? | |

| Kalpakkam 2 & 3 | Tamil Nadu | FBR x 2 | 500 | Bhavini | 2014 | 2019-20 |

| Subtotal planned | 18 units | 15,700 -17,300 MWe | ||||

| Kudankulam 7 & 8 | Tamil Nadu | PWR - AES 92 or AES-2006 | 1050-1200 | NPCIL | 2012? | 2017 |

| Rajauli | Bihar | PHWR x 2 | 700 | NPCIL | ||

| Mahi-Banswara | Rajasthan | PHWR x 2 | 700 | NPCIL | ||

| ? | PWR x 2 | 1000 | NPCIL/NTPC | by 2012? | 2014 | |

| Jaitapur 3 & 4 | Maharashtra | PWR - EPR | 1700 | NPCIL | 2016 | 2021-22 |

| ? | ? | FBR x 2 | 500 | Bhavini | 2017 | |

| ? | AHWR | 300 | NPCIL | 2014 | 2019 | |

| Jaitapur 5 & 6 | Maharashtra | PWR - EPR | 1600 | NPCIL | ||

| Markandi (Pati Sonapur) | Orissa | PWR 6000 MWe | ||||

| Mithi Virdi 1-2, Saurashtra region | Gujarat | 2 x AP1000? | 1250 | 2013 | 2019-20 | |

| Mithi Virdi 3-4 | Gujarat | 2 x AP100? | 1250 | 2015 | 2020-21 | |

| Pulivendula | Kadapa, Andhra Pradesh | PWR? PHWR? | 2x1000? 2x700? | NPCIL 51%, AP Genco 49% | ||

| Kovvada 1-2 | Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh | 2 x ESBWR? | 1350-1550 (1400?) | NPCIL | site works, 2014 | 2019-20 |

| Kovvada 3-4 | Andhra Pradesh | 2 x ESBWR? | 1350-1550 | NPCIL | ||

| Nizampatnam 1-6 | Guntur, Andhra Pradesh | 6x? | 1400 | NPCIL | ||

| Haripur 1-2 | West Bengal | PWR x 4 VVER-1200 | 1200 | 2014 | 2019-21 | |

| Haripur 3-4 | West Bengal | PWR x 4 VVER1200 | 1200 | 2017 | 2022-23 | |

| Chutka | Madhya Pradesh | ? | 1400 | BHEL-NPCIL-GE? | ||

| Mithi Virdi 5-6 | Gujarat | |||||

| Kovvada 5-6 | Andhra Pradesh | |||||

| Subtotal proposed | approx 39 | 45,000 MWe approx | ||||

For WNA reactor table: first 20 units 'planned', next (estimated) 40 'proposed'.

Nuclear Energy Parks

In line with past practice such as at the eight-unit Rajasthan nuclear plant, NPCIL intends to set up five further "Nuclear Energy Parks", each with a capacity for up to eight new-generation reactors of 1,000 MWe, six reactors of 1600 MWe or simply 10,000 MWe at a single location. By 2032, 40-45 GWe would be provided from these five. NPCIL says it is confident of being able to start work by 2012 on at least four new reactors at all four sites designated for imported plants.

The new energy parks are to be:

Kudankulam in Tamil Nadu: three more pairs of Russian VVER units, making 9200 MWe. Environmental approval has been given for the first four. A general framework agreement for construction of units 3 & 4 was planned to be signed by the end of June 2010, but has apparently been delayed on account of supplier liability questions. Equipment supply and service contracts for units 3 &4 were to be signed by the end of December 2010 and the first concreting was expected by the end of June 2011.

Jaitapur in Maharashtra: An EUR 7 billion framework agreement with Areva was signed in December 2010 for the first two EPR reactors, to be commissioned in 2017-18, along with 25 years supply of fuel. Environmental approval has been given for these, and site work will start in 2011 with a view to 2013 construction start. In July 2009 Areva submitted a bid to NPCIL to build the first two EPR units, which will have Alstom turbine-generators, accounting for about 30% of the total EUR 7 billion plant cost. The site will host six units, providing 9600 MWe.

Mithi Virdi (or Chayamithi Virdi) in Gujarat: to host US technology (possibly Westinghouse AP1000, maybe GE Hitachi ESBWR), six units. NPCIL says it has initiated pre-project activities here, with groundbreaking planned for 2012.

Kovvada in Andhra Pradesh: to host US technology (possibly GE Hitachi ESBWR), six units. NPCIL says it has initiated pre-project activities here, with groundbreaking planned for 2012. GE Hitachi said it expected to sign a contract in 2010 to supply six ESBWRs to NPCIL.

Haripur in West Bengal: to host four or six further Russian VVER-1200 units, making 4800 MWe. NPCIL says it has initiated pre-project activities here, with groundbreaking planned for 2012. Persistent rumours suggest local opposition and a likely change of site to Orissa.

Kumharia or Gorakhpur in Haryana is earmarked for four indigenous 700 MWe PHWR units and the AEC had approved the state's proposal for a 2800 MWe nuclear power plant. The inland northern state of Haryana is one of the country's most industrialized and has a demand of 8900 MWe, but currently generates less than 2000 MWe and imports 4000 MWe. The village of Kumharia is in Fatehabad district and the plant may be paid for by the state government or the Haryana Power Generation Corp. NPCIL says it has initiated pre-project activities here, with groundbreaking planned for 2012.

Bargi or Chuttka in inland Madhya Pradesh is also designated for two indigenous 700 MWe PHWR units. NPCIL says it has initiated pre-project activities here, with groundbreaking planned for 2012.

At Markandi (Pati Sonapur) in Orissa there are plans for up to 6000 MWe of PWR capacity. Major industrial developments are planned in that area and Orissa was the first Indian state to privatise electricity generation and transmission. State demand is expected to reach 20 billion kWh/yr by 2010.

Rosatom expects to build six further Russian VVER reactors at a further site, not yet identified.

The AEC has also mentioned possible new nuclear power plants in Bihar and Jharkhand.

NTPC Plans

India's largest power company, National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC) in 2007 proposed building a 2000 MWe nuclear power plant to be in operation by 2017. It would be the utility's first nuclear plant and also the first conventional nuclear plant not built by the government-owned NPCIL. This proposal became a joint venture set up in April 2010 with NPCIL holding 51%, and possibly extending to multiple projects utilising local and imported technology. One of the sites earmarked for a pair of 700 MWe PHWR units in Haryana or Madhya Pradesh may be allocated to the joint venture.

NTPC says it aims by 2014 to have demonstrated progress in "setting up nuclear power generation capacity", and that the initial "planned nuclear portfolio of 2000 MWe by 2017" may be greater. NTPC, now 89.5% government-owned, is planning to increase its total installed capacity from 30 to 50 GWe by 2012 (72% of it coal) and 75 GWe by 2017. It is also forming joint ventures in heavy engineering.

NTPC is reported to be establishing a joint venture with NPCIL and BHEL to sell India's largely indigenous 220 MWe heavy water power reactor units abroad, possibly in contra deals involving uranium supply from countries such as Namibia and Mongolia.

Other indigenous arrangements

The 87% state-owned National Aluminium Company (Nalco) has signed an agreement with NPCIL relevant to its hopes of building a 1400 MWe nuclear power plant on the east coast, in Orissa's Ganjam district. It already has its own 1200 MWe coal-fired power plant in the state at Angul to serve its refinery and smelter of 345,000 tpa, being expanded to 460,000 tpa (requiring about 1 GWe of constant supply). A more specific agreement is expected. Its interest in taking 49% of Kakrapar 3 & 4 for Rs 1800 crore ($403 million) is reported. Early in 2011 Nalco was reported to be seeking to buy uranium mines in Canada, Namibia or Mongolia

India's national oil company, Indian Oil Corporation Ltd (IOC), in November 2009 joined with NPCIL in an agreement "for partnership in setting up nuclear power plants in India." The initial plant envisaged was to be at least 1000 MWe, and NPCIL would be the operator and at least 51% owner. In November 2010 IOC agreed to take a 26% stake in Rajasthan 7 & 8 (2x700 MWe) as a joint venture, with the option to increase this to 49%. The estimated project cost is Rs 12,320 crore (123 billion rupees, $2.7 billion), and the 26% will represent only 2% of IOC's capital budget in the 11th plan to 2012. The formal JV agreement was signed in January 2011.

The cash-rich Oil and Natural Gas Corporation (ONGC), which (upstream of IOC) provides some 80% of the country's crude oil and natural gas and is 84% government-owned, is having talks with AEC about becoming a minority partner with NPCIL on 700 MWe PHWR projects.

Indian Railways have also approached NPCIL to set up a joint venture to build two 500 MWe PHWR nuclear plants on railway land for their own power requirements. The Railways already have a joint venture with NTPC - Bhartiya Rail Bijlee Company - to build a 1000 MWe coal-fired power plant at Nabinagar in Aurangabad district of Bihar, with the 250 MWe units coming on line 2012-13. The Railways also plans to set up another 1320 MWe power plant at Adra in Purulia district of West Bengal for traction supply at economical tariff.

The Steel Authority of India Ltd (SAIL) and NPCIL are discussing a joint venture to build a 700 MWe PHWR plant. The site will be chosen by NPCIL, in Gujarat of elsewhere in western India.

The government has announced that it intends to amend the law to allow private companies to be involved in nuclear power generation and possibly other aspects of the fuel cycle, but without direct foreign investment. In anticipation of this, Reliance Power Ltd, GVK Power & Infrastructure Ltd and GMR Energy Ltd are reported to be in discussion with overseas nuclear vendors including Areva, GE-Hitachi, Westinghouse and Atomstroyexport.

In September 2009 the AEC announced a version of its planned Advanced Heavy Water Reactor (AHWR) designed for export.

In August and September 2009 the AEC reaffirmed its commitment to the thorium fuel cycle, particularly thorium-based FBRs, to make the country a technological leader.

Overseas reactor vendors

As described above, there have been a succession of agreements with Russia's Atomstroyexport to build further VVER reactors. In March 2010 a 'roadmap' for building six more reactors at Kudankulam by 2017 and four more at Haripur after 2017 was agreed, bringing the total to 12. The number may be increased after 2017, in India's 13th 5-year plan. Associate company Atomenergomash (AEM) is setting up an office in India with a view to bidding for future work there and in Vietnam, and finalizing a partnership with an Indian heavy manufacturer, either L&T (see below) or another. A Russian fuel fabrication plant is also under consideration.

In February 2009 Areva signed a memorandum of understanding with NPCIL to build two, and later four more, EPR units at Jaitapur, and a formal contract is expected in December 2010. This followed the government signing a nuclear cooperation agreement with France in September 2008.

In March 2009 GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy signed agreements with NPCIL and Bharat Heavy Electricals (BHEL) to begin planning to build a multi-unit power plant using 1350 MWe Advanced Boiling Water Reactors (ABWR). In May 2009 L&T was brought into the picture. In April 2010 it was announced that the BHEL-NPCIL joint venture was still in discussion with an unnamed technology partner to build a 1400 MWe nuclear plant at Chutka in Madhya Pradesh state, with Madhya Pradesh Power Generating Company Limited (MPPGCL) the nodal agency to facilitate the execution of the project.

In May 2009 Westinghouse signed a memorandum of understanding with NPCIL regarding deployment of its AP1000 reactors, using local components (probably from L&T).

After a break of three decades, Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd (AECL) is keen to resume technical cooperation, especially in relation to servicing India's PHWRs, and there have been preliminary discussions regarding the sale of an ACR-1000.

In August 2009 NPCIL signed agreements with Korea Electric Power Co (KEPCO) to study the prospects for building Korean APR-1400 reactors in India. This could proceed following a bilateral nuclear cooperation agreement signed in October 2010.

The LWRs to be set up by these foreign companies are reported to have a lifetime guarantee of fuel supply.

Fast neutron reactors

Longer term, the AEC envisages its fast reactor program being 30 to 40 times bigger than the PHWR program, and initially at least, largely in the military sphere until its "synchronised working" with the reprocessing plant is proven on an 18-24 month cycle. This will be linked with up to 40,000 MWe of light water reactor capacity, the used fuel feeding ten times that fast breeder capacity, thus "deriving much larger benefit out of the external acquisition in terms of light water reactors and their associated fuel". This 40 GWe of imported LWR multiplied to 400 GWe via FBR would complement 200-250 GWe based on the indigenous program of PHWR-FBR-AHWR (see Thorium cycle section below). Thus AEC is "talking about 500 to 600 GWe nuclear over the next 50 years or so" in India, plus export opportunities.In 2002 the regulatory authority issued approval to start construction of a 500 MWe prototype fast breeder reactor (PFBR) at Kalpakkam and this is now under construction by BHAVINI. It is expected to start up in late 2011, fuelled with uranium-plutonium oxide (the reactor-grade Pu being from its existing PHWRs). It will have a blanket with thorium and uranium to breed fissile U-233 and plutonium respectively, taking the thorium program to stage two, and setting the scene for eventual full utilisation of the country's abundant thorium to fuel reactors. Six more such 500 MWe fast reactors have been announced for construction, four of them in parallel by 2017. Two will be at Kalpakkam, two at another site.

Initial FBRs will have mixed oxide fuel or carbide fuel, but these will be followed by metallic fuelled ones to enable shorter doubling time. One of the last of the above six is to have the flexibility to convert from MOX to metallic fuel (ie a dual fuel unit), and it is planned to convert the small FBTR to metallic fuel about 2013 (see R&D section below).

Following these will be a 1000 MWe fast reactor using metallic fuel, and construction of the first is expected to start about 2020. This design is intended to be the main part of the Indian nuclear fleet from the 2020s. A fuel fabrication plant and a reprocessing plant for metal fuels are planned for Kalpakkam, the former possibly for operation in 2014.

A December 2010 scientific and technical cooperation agreement between AEC and Rosatom is focused on "joint development of a new generation of fast reactors".

Heavy engineering in India

India's largest engineering group, Larsen & Toubro (L&T) announced in July 2008 that it was preparing to venture into international markets for supply of heavy engineering components for nuclear reactors. It formed a 20 billion rupee (US$ 463 million) venture with NPCIL to build a new plant for domestic and export nuclear forgings at its Hazira, Surat coastal site in Gujarat state. This is now under construction. It will produce 600-tonne ingots in its steel melt shop and have a very large forging press to supply finished forgings for nuclear reactors, pressurizers and steam generators, and also heavy forgings for critical equipment in the hydrocarbon sector and for thermal power plants.In the context of India's trade isolation over three decades L&T has produced heavy components for 17 of India's pressurized heavy water reactors (PHWRs) and has also secured contracts for 80% of the components for the fast breeder reactor at Kalpakkam. It is qualified by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers to fabricate nuclear-grade pressure vessels and core support structures, achieving this internationally recognised quality standard in 2007, and further ASME accreditation in 2010. It is one of about ten major nuclear-qualified heavy engineering enterprises worldwide.

Early in 2009, L&T signed four agreements with foreign nuclear power reactor vendors. The first, with Westinghouse, sets up L&T to produce component modules for Westinghouse's AP1000 reactor. The second agreement was with Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd (AECL) "to develop a competitive cost/scope model for the ACR-1000." In April it signed an agreement with Atomstroyexport primarily focused on components for the next four VVER reactors at Kudankulam, but extending beyond that to other Russian VVER plants in India and internationally. Then in May 2009 it signed an agreement with GE Hitachi to produce major components for ABWRs from its new Hazira plant. The two companies hope to utilize indigenous Indian capabilities for the complete construction of nuclear power plants including the supply of reactor equipment and systems, valves, electrical and instrumentation products for ABWR plants to be built in India. L&T "will collaborate with GEH to engineer, manufacture, construct and provide certain construction management services" for the ABWR project. Early in 2010 L&T signed an agreement with Rolls Royce to produce technology and components for light water reactors in India and internationally.

Following the 2008 removal of trade restrictions, Indian companies led by Reliance Power (RPower), NPCIL, and BHEL said that they plan to invest over US$ 50 billion in the next five years to expand their manufacturing base in the nuclear energy sector. BHEL planned to spend $7.5 billion in two years building plants to supply components for reactors of 1,600 MWe. It also plans to set up a tripartite joint venture with NPCIL and Alstom to supply turbines for nuclear plants of 700 MWe, 1,000 MWe and 1,600 MWe. In June 2010 Alstom confirmed that the equal joint venture with NPCIL and BHEL would be capitalized to EUR 25 million, to provide turbines initially for eight 700 MWe PHWR units, then for imported large units. Another joint venture is with NPCIL and a foreign partner to make steam generators for 1000-1600 MWe plants.

Two contracts awarded by NPCIL to a consortium of BHEL and Alstom cover the supply and installation of turbogenerator packages for Kakrapar 3 and 4, the first indigenously designed 700 MWe pressurised heavy water reactors. The contracts are worth over INR 16,000 million ($360 million), with BHEL's share representing around INR 8000 million ($198 million). The first contract covers the supply of the actual turbine generator packages, while the second covers associated services. BHEL and Alstom will jointly manufacture and supply the steam turbines, while BHEL will manufacture and supply the generator, moisture separator reheater and condenser, as well as undertaking the complete erection and commissioning of the turbine generator package. BHEL is also supplying steam generators for one Kakrapar unit and Rajasthan 7 & 8. It is also supplying, constructing and commissioning the complete conventional island for the 500 MWe prototype fast breeder reactor being built at Kalpakkam.

HCC (Hindustan Construction Co.) has built more than half of India's nuclear power capacity, notably all 6 units of the Rajasthan Atomic Power Project and also Kudankulam. It has a $188 million contract for Rajasthan 7 & 8.It specializes in prestressed containment structures for reactor buildings. In September 2009 it formed a joint venture with UK-based engineering and project management firm AMEC PLC to undertake consulting services and nuclear power plant construction. HCC has an order backlog worth 10.5 billion rupees ($220 million) for nuclear projects from NPCIL and expects six nuclear reactors to be tendered by the end of 2010.

Areva signed an agreement with Bharat Forge in January 2009 to set up a joint venture in casting and forging nuclear components for both export and the domestic market, by 2012. BHEL expects to join this, and in June 2010 the UK's Sheffield Forgemasters became a technical partner with BHEL in a £30 million deal. The partners have shortlisted Dahej in Gujarat, and Krishnapatnam and Visakhapatnam in Andhra Pradesh as possible sites.

In August 2010 GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy (GEH) signed a preliminary agreement with India’s Tata Consulting Engineers, Ltd. to explore potential project design and workforce development opportunities in support of GEH’s future nuclear projects in India - notably the proposals for six ESBWR units - and around the world.

See also India section of Heavy Manufacturing paper.

Uranium resources in India

India's uranium resources are modest, with 73,000 tonnes U as reasonably assured resources (RAR) and 33,000 tonnes as inferred resources in situ (to $130/kgU) at January 2009. Accordingly, from 2009 India is expecting to import an increasing proportion of its uranium fuel needs.

Mining and processing of uranium is carried out by Uranium Corporation of India Ltd, a subsidiary of the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE), at Jaduguda and Bhatin (since 1967), Narwapahar (since 1995) and Turamdih (since 2002) - all in Jharkhand near Calcutta. All are underground, the last two being modern. A common mill is located near Jaduguda, and processes 2090 tonnes per day of ore.

In 2005 and 2006 plans were announced to invest almost US$ 700 million to open further mines in Jharkand at Banduhurang, Bagjata and Mohuldih; in Meghalaya at Domiasiat-Mawthabah (with a mill) and in Andhra Pradesh at Lambapur-Peddagattu (with mill 50km away at Seripally), both in Nalgonda district.

In Jharkand, Banduhurang is India's first open cut mine and was commissioned in 2007. Bagjata is underground and was opened in December 2008, though there had been earlier small operations 1986-91. The Mohuldih underground mine is expected to operate from 2010. A new mill at Turamdih in Jharkhand, with 3000 t/day capacity, was commissioned in 2008.

In Andhra Pradesh there are three kinds of uranium mineralisation in the Cuddapah Basin, including unconformity-related deposits in the north of it. The northern Lambapur-Peddagattu project in Nalgonda district 110 km southeast of Hyderabad has environmental clearance for one open cut and three small underground mines (based on some 6000 tU resources at about 0.1%U) but faces local opposition. In August 2007 the government approved a new US$ 270 million underground mine and mill at Tummalapalle near Pulivendula in Kadapa district, at the south end of the Basin and 300 km south of Hyderabad, for commissioning in 2010. Its resources have been revised upwards to 40,000 tU and first production is expected early in 2012, using alkaline leaching for the first time in India. A further northern deposit near Lambapur-Peddagattu is Koppunuru, in Guntur district.

In Meghalaya, close to the Bangladesh border in the West Khasi Hills, the Domiasiat-Mawthabah mine project (near Nongbah-Jynrin) is in a high rainfall area and has also faced longstanding local opposition partly related to land acquisition issues but also fanned by a campaign of fearmongering. For this reason, and despite clear state government support in principle, UCIL does not yet have approval from the state government for the open cut mine at Kylleng-Pyndeng-Shahiong (also known as Kylleng-Pyndengshohiong-Mawthabah and formerly as Domiasiat) though pre-project development has been authorised on 422 ha. However, federal environmental approval in December 2007 for a proposed uranium mine and processing plant here and for the Nongstin mine has been reported. There is sometimes violent opposition by NGOs to uranium mine development in the West Khasi Hills, including at Domiasiat and Wakhyn, which have estimated resources of 9500 tU and 4000 tU respectively. Tyrnai is a smaller deposit in the area. The status and geography of all these is not known.

In Karnataka, UCIL is planning a small uranium mine at Gogi in Gulbarga area from about 2012, after undertaking a feasibility study. A mill is planned for Diggi nearby. Total cost is about $122 million. Resources are sufficient for 15 years mine life, but UCIL plans also to utilise the uranium deposits in the Bhima belt from Sedam in Gulbarga to Muddebihal in Bijapur.

India's uranium mines and mills - existing and announced

| State, district | Mine | Mill | Operating from | tU per year |

| Jharkhand | Jaduguda | Jaduguda | 1967 (mine) 1968 (mill) | 175 total from mill |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Bhatin | Jaduguda | 1967 | ||

Narwapahar | Jaduguda | 1995 | ||

Bagjata | Jaduguda | 2009? | ||

| Jharkhand, East Singhbum dist. | Turamdih | Turamdih | 2003 (mine) 2008 (mill) | 190 total from mill |

Banduhurang | Turamdih | 2007 | ||

Mohuldih | Turamdih | 2011 | ||

| Meghalaya | Kylleng-Pyndeng-Shahiong (Domiasiat), Mawthabah, Wakhyn | Mawthabah | 2012, maybe 2010 | 340 |

| Andhra Pradesh, Nalgonda dist. | Lambapur-Peddagattu | Seripally /Mallapuram | 2012 | 130 |

| Andhra Pradesh, Kadapa dist. | Tummalapalle | Tummalapalle | 2011-12 | 220 |

| Karnataka, Gulbarga dist. | Gogi | Diggi | 2012? |

However, India has reasonably assured resouirces of 319,000 tonnes of thorium - about 13% of the world total, and these are intended to fuel its nuclear power program longer-term (see below).

In September 2009 largely state-owned Oil & Natural Gas Corporation ONCC proposed to form a joint venture with UCIL to explore for uranium in Assam.

Uranium imports

By December 2008, Russia's Rosatom and Areva from France had contracted to supply uranium for power generation, while Kazakhstan, Brazil and South Africa were preparing to do so. The Russian agreement was to provide fuel for PHWRs as well as the two small Tarapur reactors, the Areva agreement was to supply 300 tU.In February 2009 the actual Russian contract was signed with TVEL to supply 2000 tonnes of natural uranium fuel pellets for PHWRs over ten years, costing $780 million, and 58 tonnes of low-enriched fuel pellets for the Tarapur reactors. The Areva shipment arrived in June 2009. RAPS-2 became the first PHWR to be fuelled with imported uranium, followed by units 5 & 6 there.

In January 2009 NPCIL signed a memorandum of understanding with Kazatomprom for supply of 2100 tonnes of uranium concentrate over six years and a feasibility study on building Indian PHWR reactors in Kazakhstan. NPCIL said that it represented "a mutual commitment to begin thorough discussions on long-term strategic relationship." Under this agreement, 300 tonnes of natural uranium will come from Kazakhstan in the 2010-11 year. Another 210 t will come from Russia. A further agreement in April 2011 covered 2100 tonnes by 2014.

In September 2009 India signed uranium supply and nuclear cooperation agreements with Namibia and Mongolia. In March 2010 Russia offered India a stake in the Elkon uranium mining development in its Sakha Republic, and agreed on a joint venture with ARMZ Uranium Holding Co.

In July 2010 the Minister for Science & Technology reported that India had received 868 tU from France, Russia & Kazakhstan in the year to date: 300 tU natural uranium concentrate from Areva, 58 tU as enriched UO2 pellets from Areva, 210 tU as natural uranium oxide pellets from TVEL and 300 tU as natural uranium from Kazatomprom.

As of August 2010 the DAE said that seven reactors (1400 MWe) were using imported fuel and working at full power, nine reactors (2630 MWe) used domestic uranium.

Uranium fuel cycle

DAE's Nuclear Fuel Complex at Hyderabad undertakes refining and conversion of uranium, which is received as magnesium diuranate (yellowcake) and refined. The main 400 t/yr plant fabricates PHWR fuel (which is unenriched). A small (25 t/yr) fabrication plant makes fuel for the Tarapur BWRs from imported enriched (2.66% U-235) uranium. Depleted uranium oxide fuel pellets (from reprocessed uranium) and thorium oxide pellets are also made for PHWR fuel bundles. Mixed carbide fuel for FBTR was first fabricated by Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) in 1979.Heavy water is supplied by DAE's Heavy Water Board, and the seven plants are working at capacity due to the current building program.

A very small centrifuge enrichment plant - insufficient even for the Tarapur reactors - is operated by DAE's Rare Materials Plant at Ratnahalli near Mysore, primarily for military purposes including submarine fuel, but also supplying research reactors. It started up about 1990 and appears that it is being expanded to some 25,000 SWU/yr. Some centrifuge R&D is undertaken by BARC at Tromaby.

Fuel fabrication is by the Nuclear Fuel Complex in Hyderabad, which is setting up a new 500 t/yr PHWR fuel plant at Rawatbhata in Rajasthan, to serve the larger new reactors. Each 700 MWe reactor is said to need 125 t/yr of fuel. The company is proposing joint ventures with US, French and Russian companies to produce fuel for those reactors.

Reprocessing: Used fuel from the civil PHWRs is reprocessed by Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) at Trombay, Tarapur and Kalpakkam to extract reactor-grade plutonium for use in the fast breeder reactors. Small plants at each site were supplemented by a new Kalpakkam plant of some 100 t/yr commissioned in 1998, and this is being extended to reprocess FBTR carbide fuel. Apart from this all reprocessing uses the Purex process. A new 100 t/yr plant at Tarapur was opened in January 2011, and further capacity is being built at Kalpakkam. As of early 2011 capacity was understood to be 200 t/yr at Tarapur, 100 t/yr at Kalpakkam and 30 t/yr at Trombay, total 330 t/yr, all related to the indigenous PHWR program and not under international safeguards.

India will reprocess the used PWR fuel from the Kudankulam and other imported reactors and will keep the plutonium. This will be under IAEA safeguards, in new plants.

In 2003 a facility was commissioned at Kalpakkam to reprocess mixed carbide fuel using an advanced Purex process. Future FBRs will also have these facilities co-located.

The PFBR and the next four FBRs to be commissioned by 2020 will use oxide fuel. After that it is expected that metal fuel with higher breeding capability will be introduced and burn-up is intended to increase from 100 to 200 GWd/t.

To close the FBR fuel cycle a fast reactor fuel cycle facility was planned, with construction to begin in 2008 and operation to coincide with the need to reprocess the first PFBR fuel. In 2010 the AEC said that used mixed carbide fuel from the Fast Breeder Test Reactor (FBTR) with a burn-up of 155 GWd/t was reprocessed in the Compact Reprocessing facility for Advanced fuels in Lead cells (CORAL). Thereafter, the fissile material was re-fabricated as fuel and loaded back into the reactor, thus 'closing' the fast reactor fuel cycle.

In April 2010 it was announced that 18 months of negotiations with the USA had resulted in agreement to build two new reprocessing plants to be under IAEA safeguards, likely located near Kalpakkam and near Mumbai - possibly Trombay. In July 2010 an agreement was signed with the USA to allow reprocessing of US-origin fuel at one of these facilities. Later in 2010 the AEC said that India has commenced engineering activities for setting up of an Integrated Nuclear Recycle Plant with facilities for both reprocessing of used fuel and waste management.

Under plans for the India-specific safeguards to be administered by the IAEA in relation to the civil-military separation plan several fuel fabrication facilities will come under safeguards.

Thorium fuel cycle development in India

The long-term goal of India's nuclear program has been to develop an advanced heavy-water thorium cycle.The first stage of this employs the PHWRs fuelled by natural uranium, and light water reactors, to produce plutonium.Stage 2 uses fast neutron reactors burning the plutonium to breed U-233 from thorium. The blanket around the core will have uranium as well as thorium, so that further plutonium (ideally high-fissile Pu) is produced as well as the U-233.

Then in stage 3, Advanced Heavy Water Reactors (AHWRs) burn the U-233 from stage 2 and this plutonium with thorium, getting about two thirds of their power from the thorium.

In 2002 the regulatory authority issued approval to start construction of a 500 MWe prototype fast breeder reactor at Kalpakkam and this is now under construction by BHAVINI. It is expected to be operating in 2012, fuelled with uranium-plutonium oxide (the reactor-grade Pu being from its existing PHWRs). It will have a blanket with thorium and uranium to breed fissile U-233 and plutonium respectively. This will take India's ambitious thorium program to stage 2, and set the scene for eventual full utilisation of the country's abundant thorium to fuel reactors. Six more such 500 MWe fast reactors have been announced for construction, four of them by 2020.

So far about one tonne of thorium oxide fuel has been irradiated experimentally in PHWR reactors and has reprocessed and some of this has been reprocessed, according to BARC. A reprocessing centre for thorium fuels is being set up at Kalpakkam.

Design is largely complete for the first 300 MWe AHWR, which was intended to be built in the 11th plan period to 2012, though no site has yet been announced. It will have vertical pressure tubes in which the light water coolant under high pressure will boil, circulation being by convection. A large heat sink - "Gravity-driven water pool" - with 7000 cubic metres of water is near the top of the reactor building. In April 2008 an AHWR critical facility was commissioned at BARC “to conduct a wide range of experiments, to help validate the reactor physics of the AHWR through computer codes and in generating nuclear data about materials, such as thorium-uranium 233 based fuel, which have not been extensively used in the past.” It has all the components of the AHWR’s core including fuel and moderator, and can be operated in different modes with various kinds of fuel in different configurations.

In 2009 the AEC announced some features of the 300 MWe AHWR: It is mainly a thorium-fuelled reactor with several advanced passive safety features to enable meeting next-generation safety requirements such as three days grace period for operator response, elimination of the need for exclusion zone beyond the plant boundary, 100-year design life, and high level of fault tolerance. The advanced safety characteristics have been verified in a series of experiments carried out in full-scale test facilities. Also, per unit of energy produced, the amount of long-lived minor actinides generated is nearly half of that produced in current generation Light Water Reactors. Importantly, a high level of radioactivity in the fissile and fertile materials recovered from the used fuel of AHWR, and their isotopic composition, preclude the use of these materials for nuclear weapons. In mid 2010 a pre-licensing safety appraisal had been completed by the AERB and site selection was in progress. The AHWR can be configured to accept a range of fuel types including enriched U, U-Pu MOX, Th-Pu MOX, and U-233-Th MOX in full core.

At the same time the AEC announced an LEU version of the AHWR. This will use low-enriched uranium plus thorium as a fuel, dispensing with the plutonium input. About 39% of the power will come from thorium (via in situ conversion to U-233, cf two thirds in AHWR), and burn-up will be 64 GWd/t. Uranium enrichment level will be 19.75%, giving 4.21% average fissile content of the U-Th fuel. While designed for closed fuel cycle, this is not required. Plutonium production will be less than in light water reactors, and the fissile proportion will be less and the Pu-238 portion three times as high, giving inherent proliferation resistance. The design is intended for overseas sales, and the AEC says that "the reactor is manageable with modest industrial infrastructure within the reach of developing countries".

Radioactive Waste Management in India

Radioactive wastes from the nuclear reactors and reprocessing plants are treated and stored at each site. Waste immobilisation plants are in operation at Tarapur and Trombay and another is being constructed at Kalpakkam. Research on final disposal of high-level and long-lived wastes in a geological repository is in progress at BARC.Regulation and safety

The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was established in 1948 under the Atomic Energy Act as a policy body. Then in 1954 the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) was set up to encompass research, technology development and commercial reactor operation. The current Atomic Energy Act is 1962, and it permits only government-owned enterprises to be involved in nuclear power.The DAE includes NPCIL, Uranium Corporation of India (UCIL, mining and processing), Electronics Corporation of India Ltd (reactor control and instrumentation) and BHAVIN* (for setting up fast reactors). The DAE also controls the Heavy Water Board for production of heavy water and the Nuclear Fuel Complex for fuel and component manufacture.

* Bhartiya Nabhikiya Vidyut Nigam Ltd

The Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB) was formed in 1983 and comes under the AEC but is independent of DAE. It is responsible for the regulation and licensing of all nuclear facilities, and their safety and carries authority conferred by the Atomic Energy Act for radiation safety and by the Factories Act for industrial safety in nuclear plants.

NPCIL is an active participant in the programmes of the World Association of Nuclear Operators (WANO).

Nuclear liability

India's 1962 Atomic Energy Act says nothing about liability or compensation in the event of an accident. Also, India is not a party to the relevant international nuclear liability conventions (the IAEA's 1997 Amended Vienna Convention and 1997 Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage - CSC). Since all civil nuclear facilities are owned and must be majority-owned by the Central Government (NPCIL and BHAVINI, both public sector enterprises), the liability issues arising from these installations are its responsibility. On 10 September 2008 the government assured the USA that India "shall take all steps necessary to adhere to the Convention on Supplementary Compensation (CSC)". Under existing Indian legislation, foreign suppliers may face unlimited liability, which prevents them from taking insurance cover, though contracts for Kudankulam 1&2 exclude this supplier liability.A bill related to third party liability has been passed by both houses of parliament. This is framed and was debated in the context of strong national awareness of the Bhopal disaster in 1984, probably the world's worst industrial accident. A Union Carbide (51% US-owned) chemical plant in the central Madhya Pradesh state released a deadly mix of methyl isocyanate and other gases due to operator error and poor plant design, killing some 15,000 people and badly affecting some 100,000 others. The company paid out some US$ 1 billion in compensation - widely considered inadequate.

The new bill places responsibility for any nuclear accident with the operator, as is standard internationally, and limits total liability to 300 million SDR (about US$ 450 million) "or such higher amount that the Central Government may specify by notification". Operator liability is capped at Rs 1500 crore (about US$ 330 million) or such higher amount that the Central Government may notify, beyond which the Central Government is liable.

However, after compensation has been paid by the operator (or its insurers), the bill allows the operator to have legal recourse to the supplier for up to 80 years after the plant starts up if the "nuclear incident has resulted as a consequence of an act of supplier or his employee, which includes supply of equipment or material with patent or latent defects of (or?) sub-standard services." This clause giving recourse to the supplier for an operational plant is contrary to international conventions.

At the same time it is reported that negotiations with Russia for additional nuclear reactors at Kudankulam are held up because of this sub-clause, in this case involving Atomstroyexport. The original Kudankulam agreement said that supplier liability ended with delivery of the plant. US diplomatic sources are similarly opposed to supplier liability after delivery.

The bill does not make any mention of India ratifying the Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage (CSC), and any international treaty or framework governing nuclear liability under which the supplier cannot be sued in their home country. The CSC is not yet in force internationally, but Indian ratification would bring it closer to being so, and was part of the September 2008 agreement with USA. In October 2010 India signed the CSC.

In October 2010 it was reported that NPCIL proposed to set up a fund of Rs 1500 crore ($336 million) for nuclear liability "with the Centre addressing anything over this level".

Research & Development

An early AEC decision was to set up the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) at Trombay near Mumbai. A series of 'research' reactors and critical facilities was built here: APSARA (pool-type, 1 MW, operating from 1956) was the first research reactor in Asia, CIRUS (40 MW, 1960) built under the Colombo Plan, and Dhruva (100 MW, 1985) followed it along with fuel cycle facilities. CIRUS uses natural uranium fuel, is moderated by heavy water and cooled by light water. It was extensively refurbished and then recommissioned in 2002. Dhruva was fully designed and built indigenously, and uses metallic uranium fuel with heavy water as moderator and coolant. Dhruva is extensively used in neutron beam research studies involving material science and nuclear fission processes. As well as research uses, the CIRUS and Dhruva units are assumed to be largely for military purposes, as is the plutonium plant commissioned in 1965. The government undertook to shut down CIRUS at the end of 2010.Reprocessing of used fuel was first undertaken at Trombay in 1964. When opening the new reprocessing plant at Tarapur in 2011, the prime minister reminded listeners that "The recycling and optimal utilization of uranium is essential to meet our current and future energy security needs."

BARC is also responsible for the transition to thorium-based systems and in particular is developing the 300 MWe AHWR as a technology demonstration project. This will be a vertical pressure tube design with heavy water moderator, boiling light water cooling with passive safety design and thorium-plutonium based fuel (described more fully above). A large critical facility to validate the reactor physics of the AHWR core has been commissioned at BARC, and by the end of 2010 BARC planned to have a research laboratory at Tarapur to test various AHWR systems.

Zerlina was an experimental reactor running 1961-83 using natural uranium fuel and heavy water moderator to test concepts for PHWRs.

A series of three Purnima research reactors have explored the thorium cycle, the first (1971) running on plutonium fuel fabricated at BARC, the second and third (1984 & 1990) on U-233 fuel made from thorium - U-233 having been first separated in 1970. All three are now decommissioned.

In 1998 a 500 keV accelerator was commissioned at BARC for research on accelerator-driven subcritical systems (ADS) as an option for stage three of the thorium cycle.

There are plans for a new 20-30 MWt multi-purpose research reactor (MPRR) for radioisotope production, testing nuclear fuel and reactor materials, and basic research. It will use fuel enriched to 19.9% U-235 and is to be capable of conversion to an accelerator-driven system later.

Design studies are proceeding for a 200 MWe PHWR accelerator-driven system (ADS) fuelled by natural uranium and thorium. Uranium fuel bundles would be changed after about 7 GWd/t burn-up, but thorium bundles would stay longer, with the U-233 formed adding reactivity. This would be compensated for by progressively replacing some uranium with thorium, so that ultimately there is a fully-thorium core with in situ breeding and burning of thorium. This is expected to mean that the reactor needs only 140 tU through its life and achieves a high burnup of thorium - about 100 GWd/t. The disadvantage is that a 30 MW accelerator is required to run it.

The Indira Gandhi Centre for Atomic Research (IGCAR) at Kalpakkam was set up in 1971. Two civil research reactors here are preparing for stage two of the thorium cycle. BHAVINI is located here and draws upon the centre's expertise and that of NPCIL in establishing the fast reactor program.

The 40 MWt fast breeder test reactor (FBTR) based on the French Rapsodie FBR design has been operating since 1985. It has achieved 165 GWday/tonne burnup with its carbide fuel (70% PuC + 30% UC) without any fuel failure. In 2005 the FBTR fuel cycle was closed, with the reprocessing of 100 GWd/t fuel - claimed as a world first. This has been made into new mixed carbide fuel for FBTR. Prototype FBR fuel which is under irradiation testing in FBTR has reached a burnup of 90 GWd/tonne. As part of developing higher-burnup fuel for PHWRs, mixed oxide (MOX) fuel is being used experimentally in FBTR, which has been operating with a hybrid core of mixed carbide and mixed oxide fuel (the high-Pu MOX forming 20% of the core).

In 2011 FBTR was given a 20-year life extension, to 2030, and IGCAR said that its major task over this period would be large-scale irradiation of the advanced metallic fuels and core structural materials required for the next generation fast reactors with high breeding ratios (the PFBR uses MOX fuel, but later versions will use metal.).

A 300 MWt, 150 MWe fast breeder reactor as a test bed for using metallic fuel is envisaged once several MOX-fuelled fast reactors are in operation. This successor to FBTR will use U-Pu alloy or U-Pu-Zr, with electrometallurgical reprocessing. Its design is to be completed by 2017.

Also at IGCAR, the tiny Kamini (Kalpakkam mini) reactor is exploring the use of thorium as nuclear fuel, by breeding fissile U-233. It is the only reactor in the world running on U-233 fuel, according to DAE.

A Compact High-Temperature Reactor (CHTR) is being designed to have long (15 year) core life and employ liquid metal (Pb-Bi) coolant. There are also designs for HTRs up to 600 MWt for hydrogen production and a 5 MWt multi-purpose nuclear power pack.

The Board of Radiation & Isotope Technology (BRIT) was separated from BARC in 1989 and is responsible for radioisotope production. The research reactors APSARA, CIRUS and Dhruva are used, along with RAPS for cobalt-60. A regular supply of isotopes for various uses commenced in early 1960s after CIRUS became operational. At present the reactors supply some 1250 user institutions with preparations of Mo-99 , I-131 , I-125, P -32 , S-35, Cr-51 , Co-60, Au-198, Br-82, Ir-192 and others.

BARC has used nuclear techniques to develop 37 genetically-modified crop varieties for commercial cultivation. A total of 15 sterilising facilities, particularly for preserving food, are now operational with more under construction. Radiation technology has also helped India increase its exports of food items, including to the most developed markets in the world.

India's hybrid Nuclear Desalination Demonstration Plant (NDDP) at Kalpakkam, comprises a Reverse Osmosis (RO) unit of 1.8 million litres per day commissioned in 2002 and a Multi Stage Flash (MSF) desalination unit of 4.5 million litres per day, as well as a barge-mounted RO unit commissioned recently, to help address the shortage of water in water-stressed coastal areas. It uses about 4 MWe from the Madras nuclear power station.

Non-proliferation, US-India agreement and Nuclear Suppliers' Group

India's nuclear industry has been largely without IAEA safeguards, though four nuclear power plants (see above) have been under facility-specific arrangements related to India's INFCIRC/66 safeguards agreement with IAEA. However, in October 2009 India's safeguards agreement with the IAEA became operational, with the government confirming that 14 reactors will be put under the India Specific Safeguards Agreement by 2014.India's situation as a nuclear-armed country excluded it from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT)* so this and the related lack of full-scope IAEA safeguards meant that India was isolated from world trade by the Nuclear Suppliers' Group. A clean waiver to the trade embargo was agreed in September 2008 in recognition of the country's impeccable non-proliferation credentials. India has always been scrupulous in ensuring that its weapons material and technology are guarded against commercial or illicit export to other countries.

* India could only join the NPT if it disarmed and joined as a Non Nuclear Weapons State, which is politically impossible. See Appendix.

Following the 2005 agreement between US and Indian heads of state on nuclear energy cooperation, the UK indicated its strong support for greater cooperation and France then Canada then moved in the same direction. The US Department of Commerce, the UK and Canada relaxed controls on export of technology to India, though staying within the Nuclear Suppliers Group guidelines. The French government said it would seek a nuclear cooperation agreement, and Canada agreed to "pursue further opportunities for the development of the peaceful uses of atomic energy" with India.

In December 2006 the US Congress passed legislation to enable nuclear trade with India. Then in July 2007 a nuclear cooperation agreement with India was finalized, opening the way for India's participation in international commerce in nuclear fuel and equipment and requiring India to put most of the country's nuclear power reactors under IAEA safeguards and close down the CIRUS research reactor at the end of 2010. It would allow India to reprocess US-origin and other foreign-sourced nuclear fuel at a new national plant under IAEA safeguards. This would be used for fuel arising from those 14 reactors designated as unambiguously civilian and under full IAEA safeguards.

The IAEA greeted the deal as being "a creative break with the past" - where India was excluded from the NPT. After much delay in India's parliament, it then set up a new and comprehensive safeguards agreement with the IAEA, plus an Additional Protocol. The IAEA board approved this in July 2008, after the agreement had threatened to bring down the Indian government. The agreement is similar to those between IAEA and non nuclear weapons states, notably Infcirc-66, the IAEA's information circular that lays out procedures for applying facility-specific safeguards, hence much more restrictive than many in India's parliament wanted.

The next step in bringing India into the fold was the consensus resolution of the 45-member Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) in September 2008 to exempt India from its rule of prohibiting trade with non-members of the NPT. A bilateral trade agreement then went to US Congress for final approval, and was signed into law on 8 October 2008. Similar agreements apply with Russia and France. The ultimate objective is to put India on the same footing as China in respect to responsibilities and trade opportunities, though it has had to accept much tighter international controls than other nuclear-armed countries.

The introduction to India's safeguards agreement says that India's access to assured supplies of fresh fuel is an "essential basis" for New Delhi's acceptance of IAEA safeguards on some of its reactors and that India has a right to take "corrective measures to ensure uninterrupted operation of its civilian nuclear reactors in the event of disruption of foreign fuel supplies." But the introduction also says that India will "provide assurance against withdrawal of safeguarded nuclear material from civilian use at any time." In the course of NSG deliberations India also gave assurances regarding weapons testing.

In October 2008 US Congress passed the bill allowing civil nuclear trade with India, and a nuclear trade agreement was signed with France. The 2008 agreements ended 34 years of trade isolation in relation to nuclear materials and technology. The CIRUS research reactor was shut down on 31 December 2010.

India's safeguards agreement was signed early in 2009, though the timeframe for bringing the extra reactors (Kakrapar 1-2 and Narora 1-2, beyond Tarapur 1 & 2, Rawatbhata 1 to 6 and Kudankulam 1 & 2) under safeguards still has to be finalised. The Additional Protocol to the safeguards agreement was agreed by the IAEA Board in March and signed in May 2009, but needs to be ratified by India. It was not yet in force at the end of 2010.

Appendix

BACKGROUND TO NUCLEAR PROLIFERATION ISSUES

India (along with Pakistan and Israel) was originally a 'threshold' country in terms of the international non-proliferation regime, possessing, or quickly capable of assembling one or more nuclear weapons: Their nuclear weapons capability at the technological level was recognised (all have research reactors at least) along with their military ambitions. Then in 1998 India and Pakistan's military capability became more overt. All three remained remained outside the 1970 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which 186 nations have now signed. This led to their being largely excluded from trade in nuclear plant or materials, except for safety-related devices for a few safeguarded facilities.India is opposed to the NPT as it now stands, since it is excluded as a Nuclear Weapons State, and has consistently criticised this aspect of the Treaty since its inception in 1970.

Regional rivalry